There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Reading exam tips that are grounded in psychological laws does more than offer strategies—it invites reflection.

When students see their exam experiences explained through evidence such as optimal arousal, cognitive load, and neural adaptation, confusion is replaced with understanding. Moments of panic, blankness, or underperformance stop feeling personal and start making sense as predictable brain responses. This shift is powerful. It encourages students to reflect on how they prepare, not just how much they study. They begin to ask better questions: when do I overload myself, when do I avoid pressure, and when am I training my brain effectively? Evidence-based insight turns exam preparation from trial-and-error into intentional practice. Instead of blaming themselves, students learn to adjust methods, calibrate stress, and build control. That reflection is the first step toward real improvement—because once students understand why their brains behave the way they do, they can change how they train them.

IB Psychology 2019 Course (Last assessment 2026) The 2019 IB Psychology course is structured around three core approaches—biological, cognitive, and sociocultural—supplemented by optional applied topics such as abnormal, health, developmental psychology, and relationships. Learning is largely content- and study-driven, with strong emphasis on understanding and evaluating key theories and classic research. Assessment rewards students who can recall studies accurately, write structured essays, and demonstrate evaluation through comparison of theories and methods. The Internal Assessment requires students to conduct and write a full experimental study, making research skills procedural and report-focused rather than interpretive. Overall, the 2019 course trains students to be competent users of established psychological knowledge.

Ref: This embedded outline is an original presentation informed by publicly available International Baccalaureate® Psychology curriculum documentation. The purpose of embed is to stimulate IB students to read IB official documents.

Helps you think through the dots and build coherent understanding.

Targeted support to resolve confusion and sharpen your thinking.

There’s a different confidence that comes when you read the authentic documents yourself, instead of depending on others’ interpretations.

Whether you are appearing for the May or November 2026 IB Psychology examinations, the learning calendar is designed to meet you exactly where you are. Content, revision, and exam strategies are paced strategically to align with each exam window, ensuring focused preparation without overload.

With thanks to the International Baccalaureate®, this calendar of May 2026 and Nov 2026 draws on their published examination timelines for student reference.

Exam readiness emerges when cognitive laws, biological mechanisms, and sociocultural support interact—optimising arousal, strengthening neural pathways, regulating stress hormones, and transforming individual effort into confident performance.

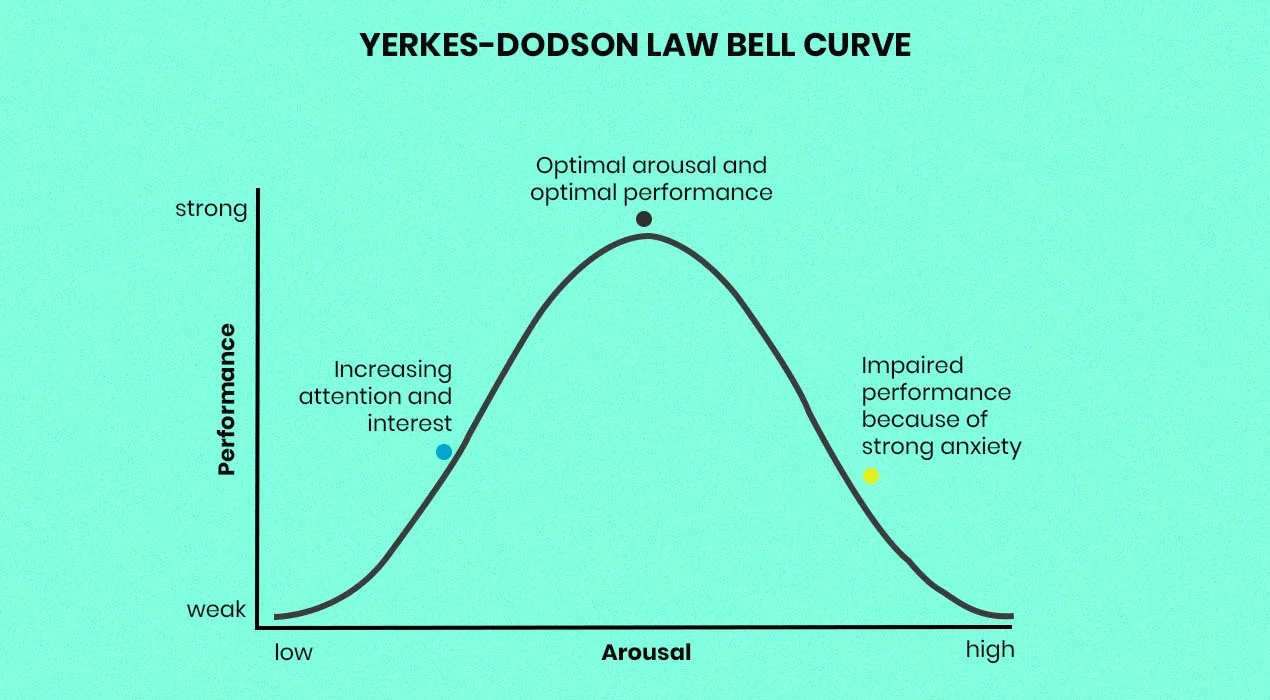

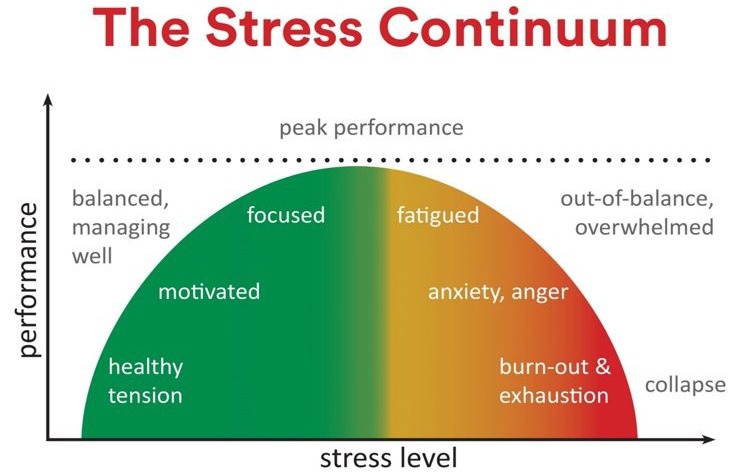

The Yerkes–Dodson Law explains that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal—but only up to an optimal point. Too little arousal leads to boredom and underperformance, while too much arousal causes anxiety and cognitive overload. In exams, students perform best when they experience moderate stress: alert enough to focus, but calm enough to think clearly, retrieve studies, and evaluate effectively. IB exams reward this optimal zone because they demand reasoning, time management, and decision-making under pressure.

Cognitive Load Theory When working memory is overloaded, performance drops. Exam readiness improves when students reduce unnecessary load (rote memorisation, cluttered notes) and focus on schema-based thinking—exactly why concept mapping and structured answers matter.

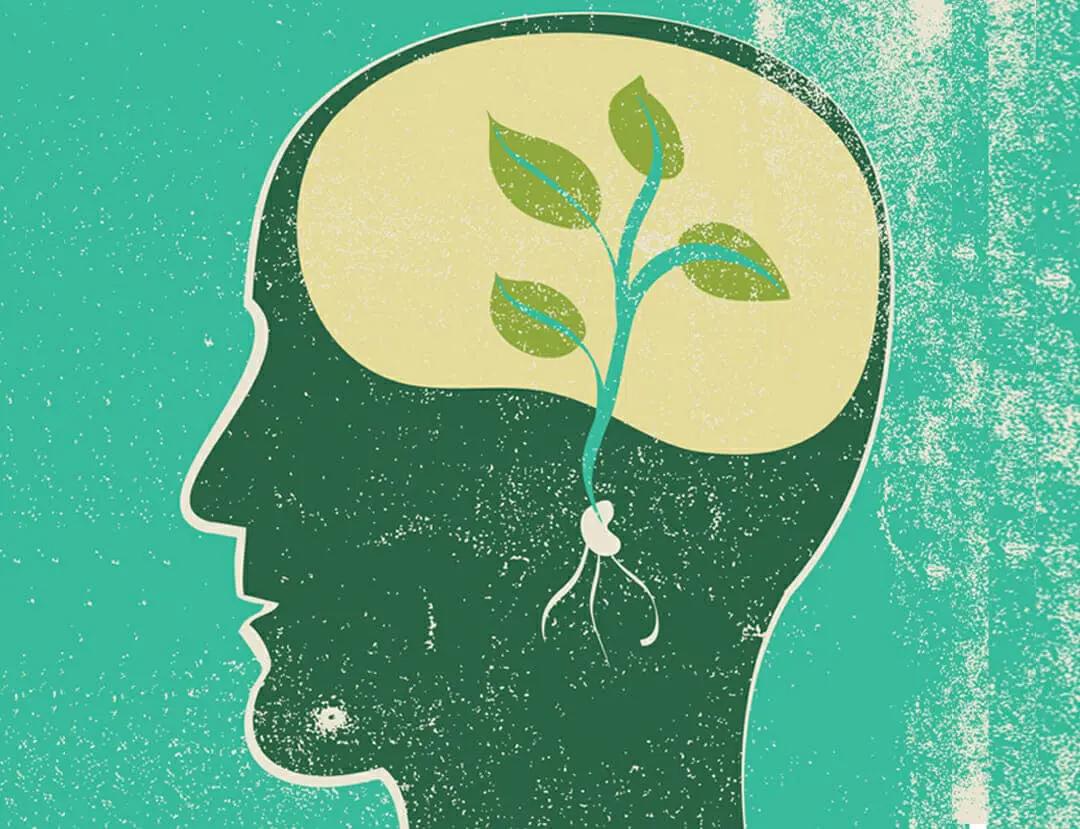

Law of Practice (Hebbian Learning) “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” Repeated practice of exam-specific tasks—like structuring SAQs, choosing studies, and evaluating—strengthens neural pathways needed during exams.

Metacognition Principle Students who monitor how they think (planning, checking relevance, adjusting answers) outperform those who only revise content. Exams reward self-regulated thinkers, not passive learners.

Retrieval Practice Effect Actively recalling information (writing answers, timed practice) strengthens memory far more than rereading. IB exams test retrieval under pressure, making this law central to readiness.

Stress–Memory Interaction (McGaugh) Moderate emotional arousal enhances memory consolidation, but extreme stress impairs retrieval. Exam training must therefore include simulated pressure, not just calm study sessions.

Cortisol Modulation Principle Moderate levels of cortisol enhance alertness and memory consolidation during exam preparation, but excessive cortisol impairs working memory and retrieval. Exam readiness improves when students practise under controlled pressure, training the brain to regulate stress rather than react to it.

Stress blackout occurs when extreme anxiety pushes arousal beyond the optimal level, overwhelming working memory and blocking retrieval. This is driven by excessive cortisol and disrupted dopamine–noradrenaline balance, explained by the Yerkes–Dodson principle, where too much stress sharply reduces performance instead of enhancing it.

Gene-Environment interaction explains that exam environments interact with genetic predispositions rather than determining outcomes. Variants of the 5-HTT serotonin transporter gene influence stress sensitivity, but supportive learning conditions and structured guidance can buffer genetic vulnerability—demonstrating that performance is shaped, not fixed.

Social Learning Theory (Sociocultural Approach) Collaborative studying improves exam readiness through observational learning, modelling, and vicarious reinforcement. Peer discussions activate oxytocin, which reduces stress and enhances trust, making concept clarification and error correction more effective in group settings.

Sociocultural Scaffolding (Vygotsky-inspired Principle) Learning within a supportive group or guided environment allows students to operate within their zone of proximal development. This shared meaning-making reduces cognitive load and promotes deeper conceptual understanding, especially when tackling complex ERQs.

Self-Efficacy Principle (Bandura) Belief in one’s ability to succeed directly affects performance. High self-efficacy is linked to dopamine reward pathways and lower cortisol responses, explaining why confidence built through structured practice translates into calmer, more controlled exam performance.

The Retrieval Practice Effect (Testing Effect) This law shows that actively retrieving information strengthens memory far more than rereading or passive revision. When students practise recalling studies, structuring SAQs, or making ERQ decisions under time pressure, neural pathways are strengthened through glutamate-driven long-term potentiation (LTP). This process is supported by dopamine, which reinforces successful retrieval, and moderated by cortisol, where moderate levels enhance focus but high levels impair recall. In exams, this law is “in action” when students who practised thinking under exam conditions outperform those who only revised content.

BDNF stands for Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, a protein produced through gene expression that supports neuron growth, synaptic strengthening, and learning-related neuroplasticity, especially in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which are crucial for memory and executive control. When students engage in sustained, effortful practice, BDNF-driven plasticity improves learning efficiency and cognitive flexibility under exam pressure.

1. Maguire et al. (2000) — London Taxi Drivers

Before:

“Why on earth did they only use right-handed London taxi drivers? Is this just a random detail I’m supposed to memorise?”

After:

“I see it now—controlling handedness reduces brain lateralisation variability, and taxi drivers ensure spatial navigation expertise. This strengthens internal validity.”

Pain point: Students memorise samples without understanding research control logic

2. Caspi et al. (2003) — Genes × Environment

Before:

“I know it’s about the 5-HTT gene and stress… but how do I actually explain this without sounding vague?”

After:

“I can clearly articulate gene–environment interaction, explain why neither genes nor environment act alone, and evaluate reductionism vs interactionism.”

Pain point: Students know “what happened” but not “how to argue it”

3. Loftus & Palmer (1974) — Eyewitness Testimony

Before:

“I keep saying ‘leading questions affect memory’… but examiners still cut marks. Why?”

After:

“I can now distinguish between reconstructive memory, schema activation, and response bias—and link each to command terms.”

Pain point: Overgeneralised explanations that don’t hit assessment criteria

4. Meaney et al. (1988) — Maternal Care & Epigenetics

Before:

“Is this genetics? Hormones? Environment? I’m confused about where this study fits.”

After:

“I can clearly explain epigenetic mechanisms, cortisol regulation, and why this study challenges genetic determinism.”

Pain point: Conceptual confusion across biological layers

5. Milner (1966) / HM — Memory Systems

Before:

“I just write ‘HM couldn’t form new memories’ and hope it’s enough.”

After:

“I can differentiate procedural vs declarative memory, link to localisation, and evaluate the ethics of irreversible neurosurgery.”

Pain point: Superficial recall instead of layered explanation

6. Bartlett (1932) vs Bahrick et al. (1975)

Before:

“Why do some memory studies feel contradictory? One says memory changes, another says it lasts decades.”

After:

“I understand that different methodologies answer different memory questions—and I can compare them without panic.”

Pain point: Students fear contradictions instead of using them for evaluation

7. Tversky & Kahneman (1974) — Cognitive Biases

Before:

“I list heuristics, but I don’t know how to evaluate them properly.”

After:

“I can explain how biases affect decision-making, link to real-life risk contexts, and evaluate ecological validity.”

Pain point: Listing terms without analytical depth

8. Rosenzweig, Bennett & Diamond (1972) — Neuroplasticity

Before:

“Isn’t neuroplasticity just ‘the brain changes’?”

After:

“I can explain enrichment, dendritic branching, limitations of animal models, and ethical implications.”

Pain point: Oversimplification of powerful concepts

9. Asch (1956) / Tajfel (1971) — Social Influence & Identity

Before:

“I confuse conformity, compliance, and social identity under exam pressure.”

After:

“I can clearly separate mechanisms, apply them to real contexts, and choose the right study for the question.”

Pain point: Conceptual overlap causing exam-time confusion

10. Research Methods (Paper 3 – HL)

Before:

“I read the stimulus but I don’t know what to look at first. I start writing definitions, then realise I’m off-track. I know methods, but I don’t know how to judge this study.”

After:

“I know where to look immediately—sampling, controls, operationalisation, ethics, and data logic. I’m not guessing; I’m making justified decisions.”

Pain point: Students know research terminology but lack the decision framework to analyse an unfamiliar study under time pressure.

etc.....

IB Psychology is not about how many studies you remember. It is about how well you select and contextually apply. Examiners reward decision-making, not data dumping. Always ask yourself:

Why this study for this question? Why not another?If you cannot justify the choice, don’t use it.

“Your brain doesn’t fail under pressure; it reveals how you trained it.”

Don’t Over-Revise on Exam Eve

Cramming pushes arousal beyond the optimal point. The brain shifts from reasoning to survival mode. Light review, structure recall, and rest keep arousal just right for retrieval the next day. The law of diminishing returns, originally from economics but widely applied to learning, explains that each additional unit of effort yields progressively smaller benefits after a certain point. In studying, early revision sessions produce large gains, but excessive repetition without rest or reflection leads to minimal improvement and rising cognitive fatigue. For IB students, this explains why the tenth practice paper often adds far less value than the third, and why strategic spacing and reflection outperform marathon revision sessions.

Challenge–threat theory explains why two students under the same level of stress can perform very differently. When stress is appraised as a challenge, the body mobilises resources efficiently and supports focused thinking. When it is appraised as a threat, physiological responses become disruptive and interfere with cognition. This theory explains why students who see exams as opportunities to apply thinking tend to stay within the optimal performance zone, while those who interpret the same pressure as danger experience panic, memory blocks, and loss of control.

The processing fluency effect explains why thinking that feels smooth is interpreted by the brain as competence. When answers are well structured, retrieval feels easier and confidence rises, even if the content level is the same. Under stress, fluency drops, and students may misjudge their own ability mid-exam, leading to further anxiety and errors. Structure restores fluency, which in turn stabilises performance. This is why clarity of process matters as much as depth of knowledge.

“When pressure feels familiar, thinking stays accessible.”

“What separates strong answers from average ones is not knowledge, but judgment under pressure.”

“Stress does not erase learning—it tests whether learning was trained to survive stress.”

“The highest form of learning is knowing when, why, and how to apply what you know.”

The inverted-U principle explains that performance improves only up to a point and then declines once effort, difficulty, or arousal exceeds what the brain can handle. This idea, closely linked to the work of Robert Yerkes and John Dodson, shows that more is not always better. In exam preparation, this means that endlessly increasing practice intensity, revision hours, or pressure does not linearly improve results. Beyond the optimal point, thinking becomes rigid, fatigue increases, and errors rise. IB students often experience this when over-revising close to exams and finding that clarity drops instead of improving.

Stop Trying to Eliminate Stress Stress is not the enemy. Too little stress leads to boredom and drift. Too much leads to panic. The Yerkes–Dodson law shows that peak performance happens in the middle zone. Your goal is not calmness—it is regulated activation. Aim to feel slightly alert, slightly tense, and mentally switched on.

Train in the “Goldilocks Zone” The brain learns best when tasks are not too easy and not too overwhelming.

Practise Stress in Small, Controlled Doses Your brain calibrates stress through exposure. If all your practice is calm, the exam feels like a shock. If all your practice is extreme, burnout follows. Use graduated stress:

Use Stress as a Signal, Not a Warning A racing heart before an exam does not mean danger—it means mobilisation. Reframing stress as “my brain is preparing” reduces cortisol spikes and keeps arousal productive. Students who interpret stress as a challenge stay closer to the optimal zone than those who interpret it as a threat.

"Planning for the first 2–3 minutes of every answer gives the brain predictability. Predictability lowers excessive stress and prevents arousal from tipping over the peak into panic."

The cognitive load threshold effect builds on cognitive load theory by explaining that working memory does not fail gradually but can collapse suddenly once its limits are exceeded. When too many decisions, ideas, or demands are processed at once, the system becomes overloaded and performance drops sharply. This is why exam blackouts feel abrupt rather than slow. Planning works because it prevents students from crossing this threshold by externalising decisions and reducing the number of simultaneous cognitive demands.

Hebbian adaptation describes how the brain changes based on repeated experience, a principle introduced by Donald Hebb. The brain strengthens whatever patterns are repeatedly activated. If students repeatedly practise under calm, low-pressure conditions, the brain adapts to calm but not to stress. If they practise thinking under manageable pressure, the brain adapts to function in that state. This explains why trained pressure reduces panic and why avoidance of stress during preparation makes exams feel overwhelming.