There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

We love neat stories about the brain. “This part controls emotions.”

“That part handles logic.”

“The left brain is analytical, the right brain is creative.” These ideas are comforting. They make the brain feel organised, predictable, almost mechanical. But psychology and neuroscience tell a far more interesting—and far less tidy—story. The truth is this: the brain does not work in isolated parts.

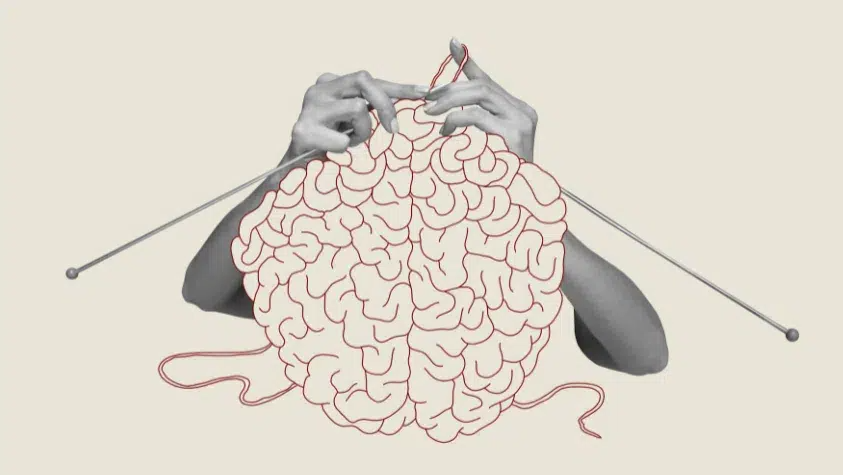

It works in networks. When students first learn about the frontal lobe, amygdala, hippocampus, or cerebellum, it’s easy to imagine each region as a character in a play, waiting for its cue. Emotion steps in here. Memory shows up there. Reason takes over somewhere else. This is the fantasy of brain parts—the belief that one area “does” one thing. In reality, almost every psychological function emerges from coordination across regions. Memory retrieval involves the hippocampus, yes—but also the prefrontal cortex (organisation), sensory areas (reconstruction), and emotional systems (salience). Emotion isn’t housed neatly in the amygdala; it is shaped by cortical interpretation, bodily feedback, and context. Even decision-making—often attributed to the prefrontal cortex—is impossible without emotional input. Patients with prefrontal damage can reason logically, yet make disastrous real-life decisions because emotional signalling is disrupted. Logic without emotion is not clarity—it’s paralysis. This matters deeply for how students understand psychology. When learners memorise “brain parts = functions,” they may score short-term marks, but they miss the discipline’s core insight: human behaviour is dynamic, distributed, and context-sensitive. IB Psychology increasingly rewards this network-based thinking, especially in questions on neuroplasticity, emotion, and cognition. The left-brain/right-brain myth is a perfect example. While certain functions show hemispheric specialisation (like language dominance), creativity, problem-solving, and reasoning are whole-brain activities. No one thinks, learns, or feels using half a brain. The myth survives because it’s simple—not because it’s accurate. Why does this fantasy persist? Because the brain is complex, and the human mind craves simplicity. Labels give us a sense of control. But psychology is not about reducing complexity—it’s about understanding it responsibly. This is also why exam answers that treat brain regions as “switches” often fall short. Strong responses explain interaction, regulation, and integration, not isolated control. They show how biology sets conditions, not outcomes. There’s something empowering in letting go of the fantasy. When students realise that learning, emotion, and thinking are products of networks that can change, the brain stops feeling fixed. Neuroplasticity makes sense. Growth becomes plausible. Mistakes feel temporary. The brain isn’t a collection of parts doing separate jobs. It’s a conversation—constantly shifting, adapting, and responding to experience. And psychology, at its best, teaches us to listen to that conversation rather than oversimplify it.

References:McIntosh, A. R. (2000). Towards a network theory of cognition.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (2014). The cognitive neurosciences.

Every learner’s IB Psychology journey is different.

Share a few details so we can guide you with clarity, care, and academic precision. Stay informed with insights on how IB Psychology builds thinking skills, confidence, and long-term understanding of simple exam strategies, clarity notes, and reflections that help you think better.

The move away from the idea that single brain parts “control” single functions was led by cognitive neuroscientists such as Anthony McIntosh and Michael Gazzaniga. Through brain-imaging and lesion studies, they showed that complex mental processes cannot be explained by isolated regions acting alone. Instead, the same brain area can participate in different functions depending on the pattern of connections it forms with other regions. Their work helped dismantle popular myths like “emotion lives in the amygdala” or “logic sits in the frontal lobe,” replacing them with a more accurate, interaction-based view of the brain.

The Theory

This perspective is known as the Network Theory of Cognition (also called distributed processing). The theory proposes that psychological functions—such as memory, emotion, decision-making, and creativity—emerge from coordinated activity across networks of brain regions, not from single locations. Brain regions act more like team members than solo performers, dynamically linking and unlinking depending on context and task demands. For students of psychology, especially in IB, this theory is crucial because it explains why strong answers focus on interaction, regulation, and integration, rather than treating brain areas as simple on–off switches.

“The brain is not hardwired; it is soft-wired by experience.”

— Norman Doidge

This quote captures the core idea that when one brain region is damaged, the brain can reorganise and reroute functions through other networks. Recovery and learning happen not by replacing a lost part, but by rewiring pathways—proof that abilities are adaptable, not fixed to single brain areas.

Brain Injury and Functional Compensation

When a brain region is damaged, the brain does not behave like a broken machine with a permanently missing part. Instead, it adapts through functional compensation, a process rooted in neuroplasticity. Research in cognitive neuroscience shows that psychological functions are distributed across networks, so when one node in the network is compromised, other regions can reorganise to support the same function in a different way. This does not mean the brain becomes “normal again,” but that it finds alternative routes to achieve similar outcomes. Studies of brain-injured patients, including work discussed by Michael Gazzaniga, show that recovery often depends on the prefrontal cortex learning to regulate behaviour more deliberately, using conscious strategies to replace automatic processing. For example, after hippocampal damage, patients may struggle with forming new memories, yet compensate by using external aids, repetition, or structured routines supported by frontal networks. Similarly, damage affecting emotional regulation can be partly compensated when cortical regions reinterpret emotional signals rather than relying on fast, automatic pathways. Importantly, compensation is effortful and context-dependent. It requires practice, feedback, and time. This is why rehabilitation focuses on training strategies rather than “fixing” a damaged area. The same principle applies to learning: when students struggle with attention, memory, or stress regulation, improvement often comes not from changing the brain directly, but from teaching the brain new ways to manage the task. Functional compensation therefore reinforces a central psychological insight—human ability is not fixed to specific brain parts but emerges from adaptable networks that can reorganise when challenged.