There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Anxiety has a terrible reputation. Students are told to eliminate it.

To calm down.

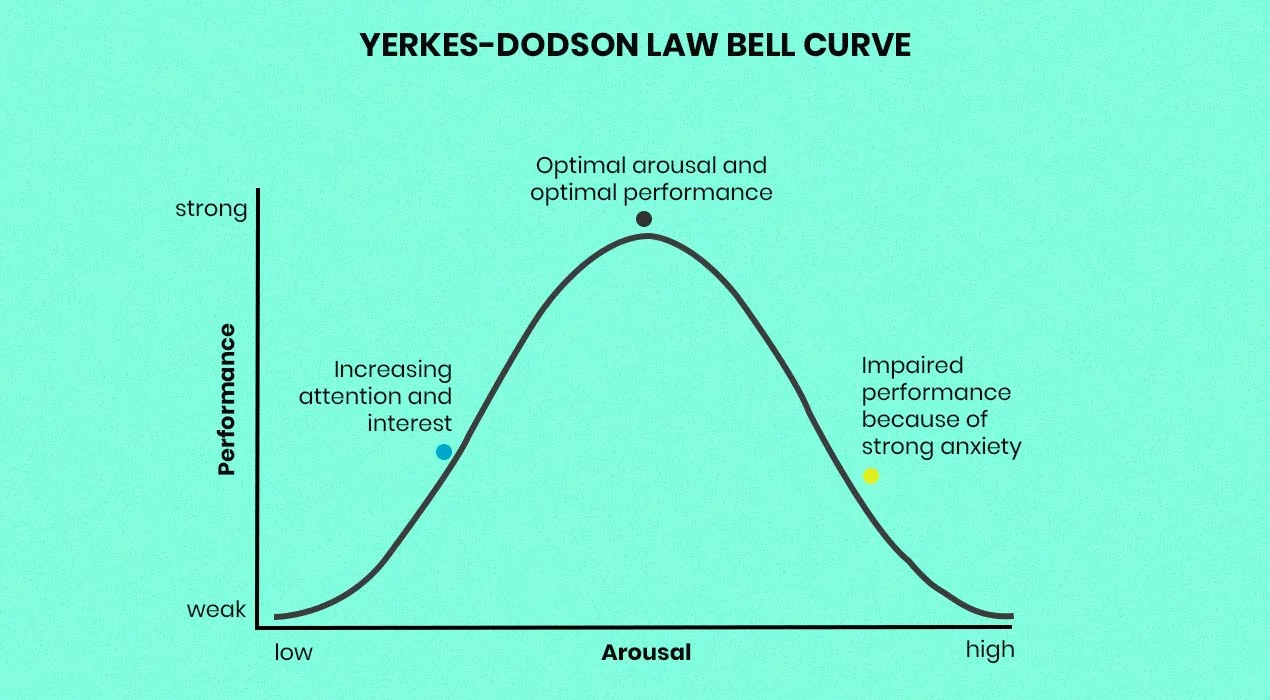

To “stop stressing.” But psychology tells a more interesting—and more honest—story. Anxiety is not automatically harmful. In the right range, it is performance-enhancing. From a biological perspective, anxiety is the brain’s way of preparing the body for challenge. When a student feels anxious before an exam, the brain releases adrenaline and noradrenaline, increasing alertness, reaction speed, and focus. At the same time, dopamine supports motivation and goal-directed behaviour. This state sharpens attention. It helps the brain prioritise what matters now. The Yerkes–Dodson law captures this perfectly: performance improves with physiological arousal up to an optimal point. Below this level, students feel bored or disengaged. Above it, thinking becomes chaotic. But in the middle—where anxiety is present but manageable—performance peaks. This explains a familiar experience:

Students often perform worse when they feel too relaxed. Low arousal reduces urgency. Focus drifts. The brain doesn’t fully mobilise its resources. Moderate anxiety, however, signals importance. It tells the brain, “Pay attention. This matters.” Cognitively, anxiety can improve selective attention. It narrows focus, reducing distraction and increasing task engagement. This is especially useful in exam situations that demand sustained concentration and rapid decision-making. Anxiety also interacts with memory. Moderate emotional arousal enhances memory consolidation, making relevant information easier to retrieve. This is why students often remember material better when they revise with mild pressure—such as timed practice—than when studying casually. So why does anxiety sometimes ruin performance? Because the problem is not anxiety itself, but loss of regulation. When anxiety becomes overwhelming, cortisol floods the system. High cortisol disrupts working memory and weakens prefrontal cortex control. The brain shifts from thoughtful reasoning to survival mode. This is when students experience panic, blanking out, or rushing through answers. The key difference lies in familiarity. Students who regularly practise under exam-like conditions teach their brains that anxiety is expected and manageable. Over time, the stress response becomes calibrated. Cortisol spikes reduce. The brain stays within the optimal performance zone. Students who avoid pressure during preparation, however, experience anxiety as a threat rather than a challenge. Their brains have no template for functioning under stress. This is why telling students to “relax” rarely helps. What helps is training under controlled pressure. When students learn how to plan answers, manage time, and make decisions while mildly anxious, anxiety stops being an enemy. It becomes a signal—not of danger, but of readiness. The goal is not to feel calm. The goal is to feel activated but in control. When anxiety works with the brain instead of against it, it sharpens thinking, strengthens memory, and improves performance. That’s not weakness. That’s biology doing its job.

References:Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation.

McGaugh, J. L. (2004). The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences.

The above blog is premised on the following psychological theories.

Together, these theories explain why the goal for IB students is not to eliminate anxiety, but to train the brain to operate optimally under it—turning anxiety into a signal of readiness rather than a source of fear.

Yerkes–Dodson Law (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908)

The Yerkes–Dodson law explains that performance increases with physiological arousal only up to an optimal point, after which further arousal leads to decline. This directly underpins the blog’s central argument that anxiety is not inherently harmful. At low arousal, students feel disengaged and unfocused; at high arousal, thinking becomes disorganized and panic-driven. However, in the middle zone—where anxiety is present but regulated—attention sharpens, urgency increases, and performance peaks. This law explains why students often perform better with mild exam tension than in a completely relaxed state, and why exams reward controlled engagement rather than emotional quietness.

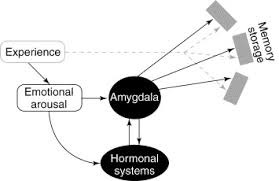

Emotional Arousal and Memory Consolidation (McGaugh, 2004)

Research by James McGaugh demonstrates that moderate emotional arousal strengthens memory consolidation through amygdala–hippocampal interactions. This theory supports the blog’s claim that mild pressure—such as timed practice—improves recall, while overly relaxed study leads to weaker memory traces. Anxiety, when kept within optimal limits, signals importance to the brain and enhances the encoding and retrieval of relevant information. Excessive arousal, however, disrupts memory processes, explaining exam blank-outs under extreme stress.

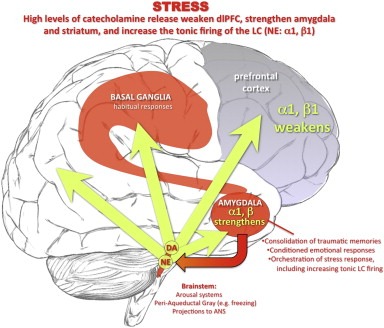

Prefrontal Cortex Regulation under Stress (Arnsten, 2009)

Neuroscientific research by Amy Arnsten explains the biological mechanism behind the Yerkes–Dodson curve. Moderate levels of stress hormones such as adrenaline, noradrenaline, and dopamine strengthen prefrontal cortex functioning, enhancing working memory, planning, and cognitive control. When stress becomes excessive, cortisol floods the system, weakening prefrontal regulation and shifting the brain into survival mode. This explains the blog’s emphasis on regulation: anxiety enhances performance only when the brain retains top-down control, and collapses performance when regulation is lost.

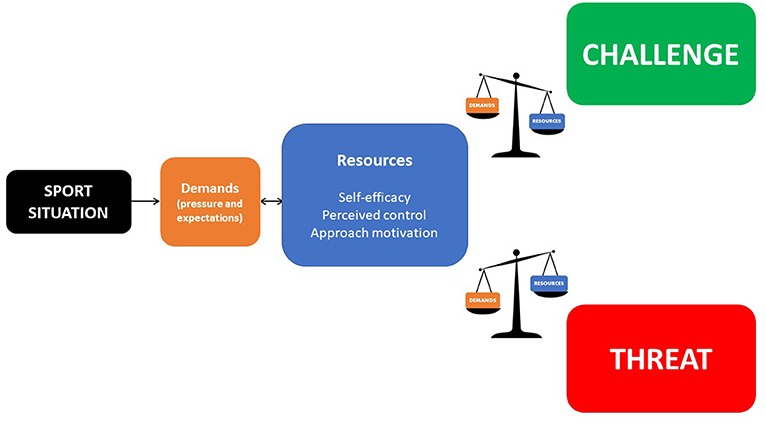

Challenge–Threat Theory of Stress (Mendes et al.)

The Challenge–Threat framework, developed by Wendy Mendes, explains why the same anxiety can either enhance or impair performance. When students interpret anxiety as a challenge, the stress response becomes efficient and performance-oriented. When anxiety is interpreted as a threat, cortisol dominance impairs cognitive control. This directly aligns with the blog’s argument that practice under exam-like conditions recalibrates the stress response, teaching the brain that anxiety is manageable and functional rather than dangerous.