There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Clarity of thoughts drives your pen's speed

Most students believe that practice alone makes answers better. So they practise.

And practise.

And practise again. But here’s the uncomfortable truth psychology reveals: repeating weak answers does not improve performance—it reinforces weakness. The brain does not magically “fix” what it repeats.

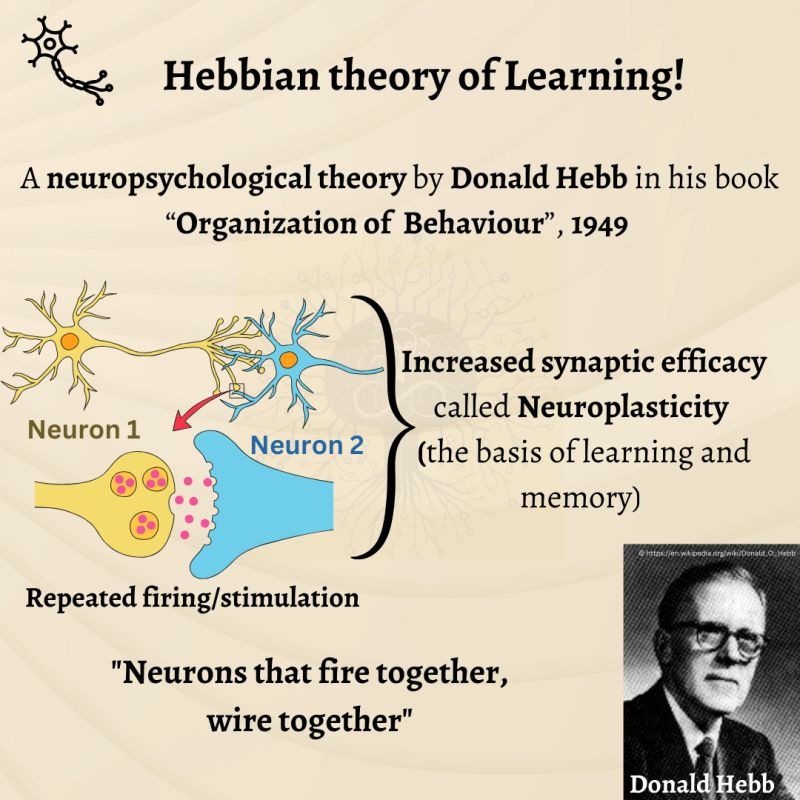

It automates what it repeats. In the first phase of preparation, the brain needs depth, not speed. This is the phase where concepts must be understood slowly, connections must be built deliberately, and confusion must be resolved—not bypassed. During this stage, the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are actively constructing accurate mental representations of the syllabus. This is where real learning happens. Rushing this phase is costly. When students begin timed writing before they truly understand what a strong answer looks like, they start practising incomplete reasoning, poor structure, and misaligned evaluation. Neurobiologically, this is dangerous practice. Each repetition strengthens synaptic pathways through Hebbian learning—neurons that fire together wire together. The brain doesn’t label an answer as “weak.”

It labels it as familiar. This is why students who practise weak answers repeatedly find it hard to suddenly write strong ones later. The brain resists change because it has already optimised the old pattern. What feels like “practice” becomes entrenched habit. This is where smart preparation differs from hard preparation. After deep learning comes a second, very specific phase: practising strong answers a limited number of times, with the sole purpose of improving writing pace and fluency, not content. At this stage, the logic is already correct. The structure already works. Practice now strengthens procedural memory, making execution smoother under time pressure. This distinction matters.

1. Deliberate Practice Theory

Discovered and developed by K. Anders Ericsson

Ericsson showed that repetition alone does not lead to expertise. What matters is deliberate practice: practising with a clear model of what “good” looks like, receiving feedback, correcting errors before repetition, and practising slowly at first. This directly supports the idea that repeating weak answers strengthens poor habits, while practising strong answers builds expertise. Blind practice stabilises errors; deliberate practice refines performance.

Advice for IB students

Do not practise answers just to feel busy—practise only after you know what a strong answer looks like. Your brain automates whatever you repeat, so repeating weak structure or unclear reasoning only locks in bad habits. First, slow down and build depth: understand concepts, command terms, and how evidence and evaluation fit together. Once the logic and structure are clear, practise selectively to build fluency under time pressure. In IB exams, quality comes before speed. Train accuracy first, then let efficiency emerge—because the brain performs best when it is executing a well-learned structure, not improvising under stress.

“Speed comes from clarity, not repetition. An exemplary exam response does not reveal how much you practised—it reveals how you practised.” -Dr. Sukanya Pal