There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

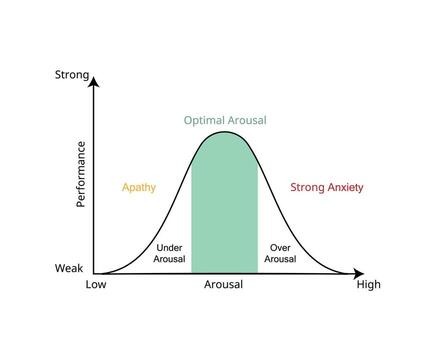

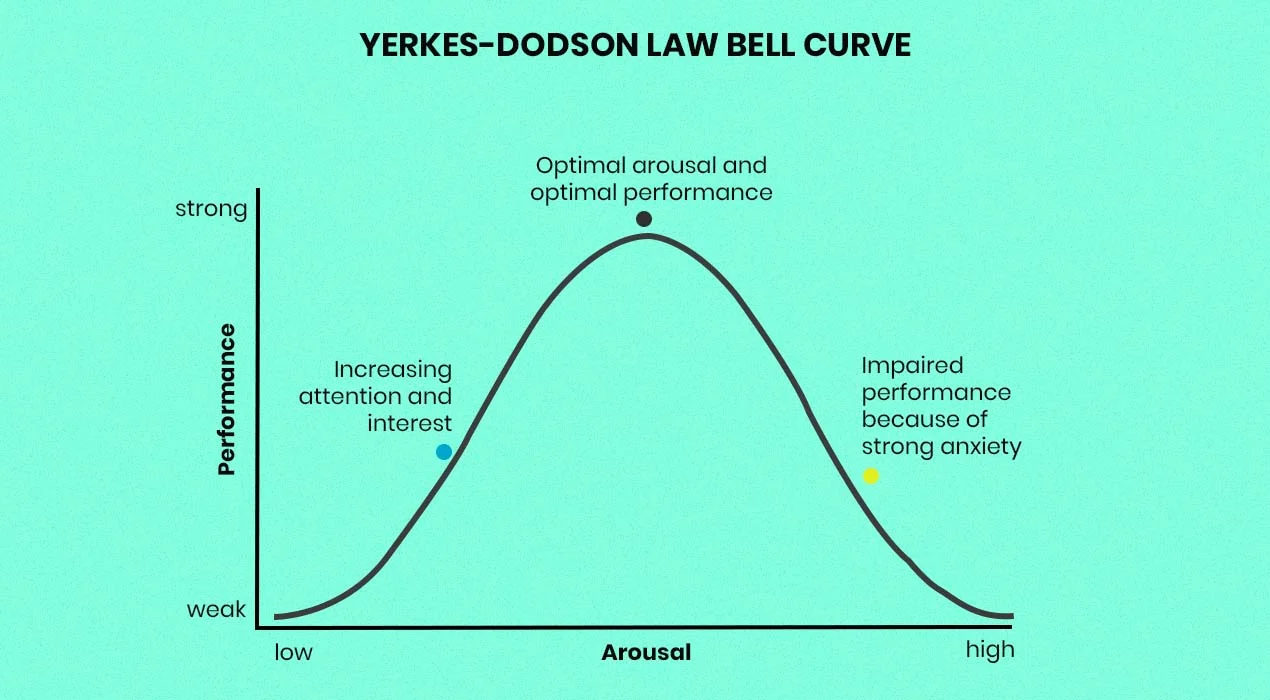

“I knew this. But!!!!Biting the finger nails often start with, “I revised everything. My mind just went blank!” Almost every IB student has said this after an exam. A blackout feels like betrayal — as if the brain suddenly refused to cooperate. But psychology tells us something more precise, and far more empowering: blackouts are not caused by lack of knowledge, but by how stress hijacks access to knowledge. When students prepare for exams, most of their effort goes into encoding information — learning studies, theories, definitions. Very little time is spent training the brain for retrieval under pressure. And retrieval is a different neurological task altogether. Under exam stress, the body releases cortisol. In moderate amounts, cortisol sharpens attention. But when stress crosses a threshold, cortisol begins to suppress activity in the hippocampus, the brain region critical for memory retrieval. At the same time, excessive arousal disrupts the balance of dopamine and noradrenaline, which are essential for focused decision-making in the prefrontal cortex. This is why blackouts feel sudden.The knowledge is still there — the access route is blocked. The Yerkes–Dodson principle explains this perfectly: performance improves with arousal only up to an optimal point. Beyond that, cognitive control collapses. IB exams sit right on that edge, where calm thinking must coexist with time pressure. Here’s where preparation style matters. Students who revise only through reading and highlighting train their brains in low-arousal conditions. When the exam introduces high arousal, the brain has no prior template for functioning there. Panic fills the gap. In contrast, students who practise planning answers, making quick choices, and writing under timed conditions repeatedly expose their brains to controlled stress. Over time, the stress response becomes regulated. Cortisol spikes reduce. Confidence increases — not emotionally, but biologically. This is neuroplasticity in action. Repeated exposure strengthens neural pathways between the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, improving emotional regulation and cognitive control. The brain learns: “I’ve been here before. I know what to do.” There’s another overlooked factor: interpretation of stress. Students who perceive stress as a threat experience stronger cortisol responses than those who see it as a challenge. When exams are framed as opportunities to apply thinking rather than tests of memory, the physiological response changes. Stress becomes activating rather than paralysing. This is why structured exam preparation reduces anxiety — not because students know more, but because their brains feel predictability and control. Blackouts are not signs of weakness.

They are signs of untrained retrieval systems. The solution is not more content.

It’s smarter exposure. When students train under realistic conditions, with guidance on how to think, exams stop feeling like ambushes. They become familiar cognitive environments — demanding, yes, but manageable. And that is when preparation finally shows up where it matters most.

References:Lupien, S. J. et al. (2007). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition.

McGaugh, J. L. (2015). Consolidating memories. Annual Review of Psychology.

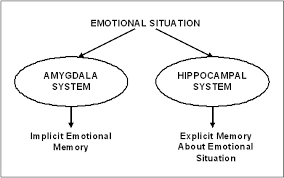

2. Emotional Arousal and Memory Modulation (McGaugh) James McGaugh discovered that emotional arousal modulates memory consolidation and retrieval through interactions between the amygdala and hippocampus. Moderate arousal strengthens memory access, but excessive arousal disrupts it. This explains why controlled exam pressure can enhance recall, while overwhelming anxiety leads to sudden blanks.

3. Yerkes–Dodson Law (Optimal Arousal Theory) Proposed by Robert Yerkes and John Dodson, this law states that performance improves with arousal only up to an optimal point, after which it declines. IB exams sit precisely at this tipping point. When arousal exceeds the optimal range, cognitive control collapses—even when knowledge is present—producing the blackout experience.

Performance collapses not because stress exists, but because thinking wasn’t trained for stress.

Levitin explains how stress narrows cognitive capacity, impairs working memory, and disrupts retrieval—exactly what happens when arousal crosses the optimal point on the Yerkes–Dodson curve. He shows why the brain performs best when thinking is pre-structured before stress hits, reinforcing your point that exams reward regulated arousal, not calmness or panic.

4. Neuroplasticity and Stress Regulation (Prefrontal–Limbic Control) Modern neuroscience, including work synthesized by Amy Arnsten, shows that repeated exposure to manageable stress strengthens prefrontal control over limbic (emotional) responses. This explains why timed practice and structured exam simulations reduce blackouts over time: the brain rewires itself to treat exam stress as familiar and controllable rather than threatening.

Blackouts happen when stress blocks access—not when knowledge is missing.

Message for IB students If your mind goes blank in an exam, it doesn’t mean you didn’t study enough. It means your brain wasn’t trained to retrieve under pressure. Exams don’t test calmness or memory alone—they test control, structure, and familiarity with stress. Practise planning before writing. Practise choosing studies quickly. Practise thinking when the clock is ticking. When you do, your brain learns, “I’ve been here before.” That familiarity reduces panic, restores access to knowledge, and brings clarity back. Confidence in an IB exam isn’t something you summon on the day—it’s something your brain recognises because you trained it to.